Communal Traditions and Naming Rituals in Rai Culture

The Rai community is widely recognized for its strong sense of kinship, mutual cooperation, and collective living. Social unity is not merely a value but a living practice reflected in everyday cultural traditions. Two significant cultural expressions of this togetherness are the communal pork-sharing custom and the traditional naming ceremony of newborns.

Communal Pork Preparation and Sharing Tradition

In Rai society, when a family decides to slaughter a pig or occasionally a buffalo or other livestock they invite neighboring households to participate in the process. This practice is not solely about meat consumption but about reinforcing communal bonds and reciprocity within the community.

The animal is prepared according to traditional Rai methods. After the butchering process is completed, portions of pork are fried as Chhokmasa or Bhutuwa (fried pork pieces). The prepared meat is then shared among those present, accompanied by Umbak (homemade millet wine). Sharing food and drink symbolizes unity, equality, and collective belonging.

Each participating household receives a portion of meat according to family size and need. If the meat is insufficient, it is divided fairly to ensure everyone receives a share. Before departing, guests formally inform the host and bid farewell with the traditional expression “Hasinchine Molo,” reflecting respect and gratitude. This practice demonstrates the Rai community’s deep-rooted principle of sharing resources and strengthening social harmony.

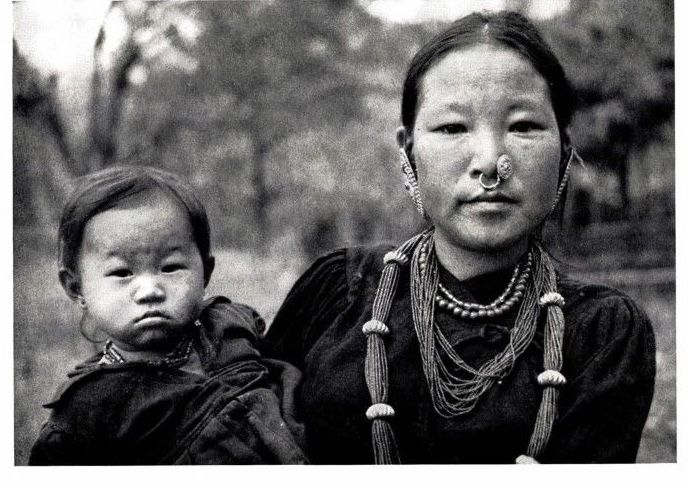

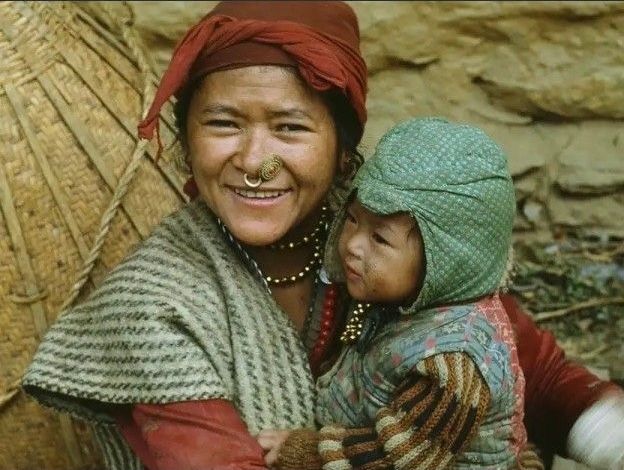

Naming Ceremony in Rai Culture

The naming ceremony is another culturally significant ritual that highlights the Rai community’s spiritual beliefs and family structure. When a woman becomes pregnant, a special batch of millet wine (Umbak) is prepared in her name. This wine is preserved for use during the postpartum naming ceremony.

The ceremony takes place on the sixth day after the birth of a baby boy and on the fifth day for a baby girl. In Rai tradition, the ritual is usually conducted by a senior woman of the family, who assumes the role of a priest. Unlike many patriarchal ritual systems, Rai culture often entrusts women with spiritual authority in domestic ceremonies.

The head woman organizes the ritual and prepares the necessary symbolic items. For a baby boy, items typically include a plough, bow and arrow (Dhanuskada), Umbak, Hengma, a cradle, knife, rooster, and thread.

Fig:1 A bamboo craft Cradle

For a baby girl, items such as a handloom comb, Charkha (spinning wheel), hen, cradle, thread, and Combi (a small knife) are prepared. These objects symbolize traditional gender roles, responsibilities, and skills within Rai society.

Ritual Process and Symbolism

During the ceremony, the senior woman chants incantations to protect both mother and child from harmful spirits. One important step involves sacrificing a rooster while reciting ritual chants. Before the mother and child enter the house, Umbak is poured onto a hot pot at the main doorway as a protective offering.

Threads fashioned into rings are tied around the newborn’s waist, hands, and legs. This act symbolizes the child’s transition from the spiritual realm to the human world. It also traditionally serves as a way to measure the baby’s growth over time.

Specially woven bamboo cradles are prepared with distinct patterns for boys and girls. The patterns such as “Raja, Ghar, Indra” and “Indra, Raja, Gharjam” carry symbolic meanings related to household identity, protection, and social roles. Weapons such as a knife (for boys) or Combi (for girls) are placed in the cradle. In Rai belief, sharp objects symbolize strength and protection, discouraging evil spirits from harming the child.

Another significant step involves pouring Chhanuwa (millet extract) into a hot pot containing oil and spices. This act serves as an offering to spirits of women who may have died during pregnancy or childbirth, requesting them not to disturb the newborn or the mother.

Cultural Significance

Each stage of the naming ceremony carries layered meanings related to protection, identity, growth, and community continuity. Together with the communal pork-sharing tradition, these practices reflect the Rai community’s emphasis on cooperation, gendered symbolism, spiritual belief, and collective responsibility.

Through such rituals, the Rai people preserve their ancestral knowledge and maintain a strong sense of cultural identity across generations.

※By Rai Sujan