Wabuk – An Importance In Khambu Rai Rituals

Culture takes diverse forms. Some appear in the shape of human activities, while others exist as material objects. In defining culture, the anthropologist E. B. Tylor, in his renowned book Primitive Culture, described it as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” This definition clearly establishes culture as a broad and comprehensive domain encompassing both tangible and intangible dimensions of human life.

Within this broader framework of cultural objects, the Chindo holds a significant place. For the Kirat Rai community, the Chindo is an important sacred object that embodies cultural identity. Rituals and ceremonies of the Kirat Rai are rarely performed without it. Despite its sacred status, there is a long-standing belief that the Chindo should not be deliberately cultivated; it is said that planted Chindo does not thrive. Instead, it is traditionally gathered from wild growth-found creeping along slopes, ridges, field embankments, and stream banks. It grows as a vine, climbing trees and shrubs when available, or spreading along the ground in their absence. When the fruit ripens-usually around the months of Mangsir and Poush (November–January)-it is harvested and preserved for ritual use.

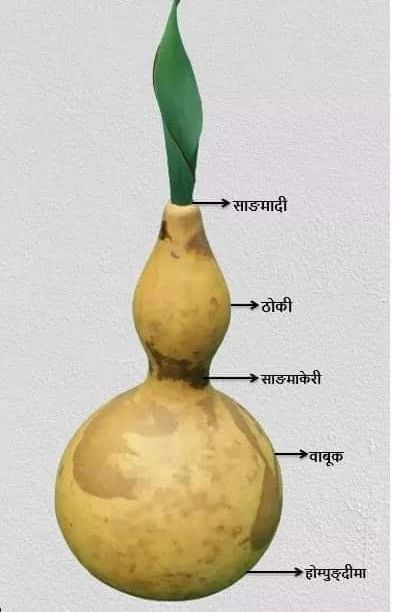

Fig:1 Specification of Wabuk (Chindo)

Botanically, the Chindo belongs to the gourd family (Cucurbitaceae). Its scientific name is Lagenaria siceraria. It thrives in warm climates and grows from the lowland Terai to the mid-hill regions. Due to linguistic diversity within the Rai community, the Chindo is known by various names: Bantawa Rai call it Wabub, Solonwa, Fubchit; Chamling Rai call it Wabu; Dungmali Rai say Wabhuk; Khaling Rai refer to it as Kyafyam; Thulung Rai call it Bom; Dumi Rai say Kharawa; Puma Rai call it Wabup; Wambule Rai refer to it as Krakrom; Chipum and Bayung Rai call it Pupum; and Sampang Rai name it Salwa. Despite these varied names, its use remains consistent across Rai subgroups.

Among the Rai, the Chindo serves two principal purposes: general/practical use and special cultural use. In everyday life, it functions as a storage container for grains and seeds, as a vessel for storing water, and for carrying traditional alcoholic beverages such as jaad (fermented millet beer) or raksi (distilled liquor). In areas where the Chindo grows, people from other communities may also use it for such practical purposes. However, its special ritual use is unique to the Kirat Rai.

Fig:2 Wabuk used as ancestral rites

In marriage and ancestral rites, the Chindo is indispensable. During marriage negotiations, the groom’s family carries sagun raksi (auspicious liquor) in a Chindo when formally requesting the bride’s hand. Bringing the liquor in any other container is considered disrespectful and may lead to rejection of the proposal. In this sense, the Chindo is directly tied to Rai honor and prestige. Once the proposal is accepted, the liquor from the Chindo is shared, marking the beginning of the marriage rites. Throughout the wedding rituals, the Chindo remains the sacred vessel for offering ritual liquor.

Similarly, in ancestral rites, offerings of marchapani (pure fermented beverage) or jaad presented to the ancestors must be kept in a Chindo. No matter how refined or modern alternative vessels may be, they are not considered acceptable. There is a belief that ancestors will not receive offerings made in containers other than the Chindo. In ritual contexts, only the household head (householder) and the Mangpa (ritual priest) are permitted to handle the Chindo. If other family members touch it, it is regarded as inauspicious, requiring immediate ritual purification or replacement with a new Chindo.

A remarkable feature of this tradition is the prominent role of women. Women hold primary rights over preparing and filling the Chindo for both marriage and ancestral ceremonies. Except in rare cases, the responsibility of filling ritual liquor into the Chindo belongs to the female head of the household. No one including the male head may perform this duty without her consent. However, this privilege is governed by strict Mundum-based norms.

Before marriage, a woman must not have had intimate relations with a man from another caste; after marriage, she must remain faithful to her husband. If the household head is a woman from a non-Rai community, she is not permitted to handle the Chindo. It is believed that violation of these norms may anger the ancestors, resulting in misfortune or illness for the individual and the family. The female household head may, however, delegate this responsibility to a Rai daughter-in-law. In doing so, a ritual must be performed in which the daughter-in-law offers a Chindo filled with liquor to her mother-in-law, bowing in respect and pledging to uphold her honor and fulfill the entrusted responsibility faithfully. Only then does she acquire the right to fill the Chindo.

The male household head may assume this role only under specific circumstances: if the female head has died, eloped, married into another caste, or if there is no eligible daughter-in-law in the household. He cannot arbitrarily claim this authority while the female head remains eligible and has not relinquished her rights. If he attempts to do so, the woman may appeal to community authority to restore her rights, and ritual procedures must be conducted to reinstate her dignity and ritual standing.

Thus, within Rai culture, the right to fill the Chindo with ritual liquor stands as a powerful example of women’s cultural authority. This tradition is expected to continue as long as the practice of worshipping ancestors at the Suptulung (ancestral hearth) endures. Historically, women also held the primary right to name children, although this practice has gradually shifted toward fathers in recent times.

The women-centered ritual authority embedded in Rai customs and Mundum traditions remains an area requiring deeper scholarly exploration. Such cultural privileges not only reinforce women’s familial and social status but also enhance their agency and decision-making power within the community.

※By Research Scholar Chandra Hatuwali